Approx. read time: 20 min.

Post: Contextualising Legal Research: Practical Methods Guide

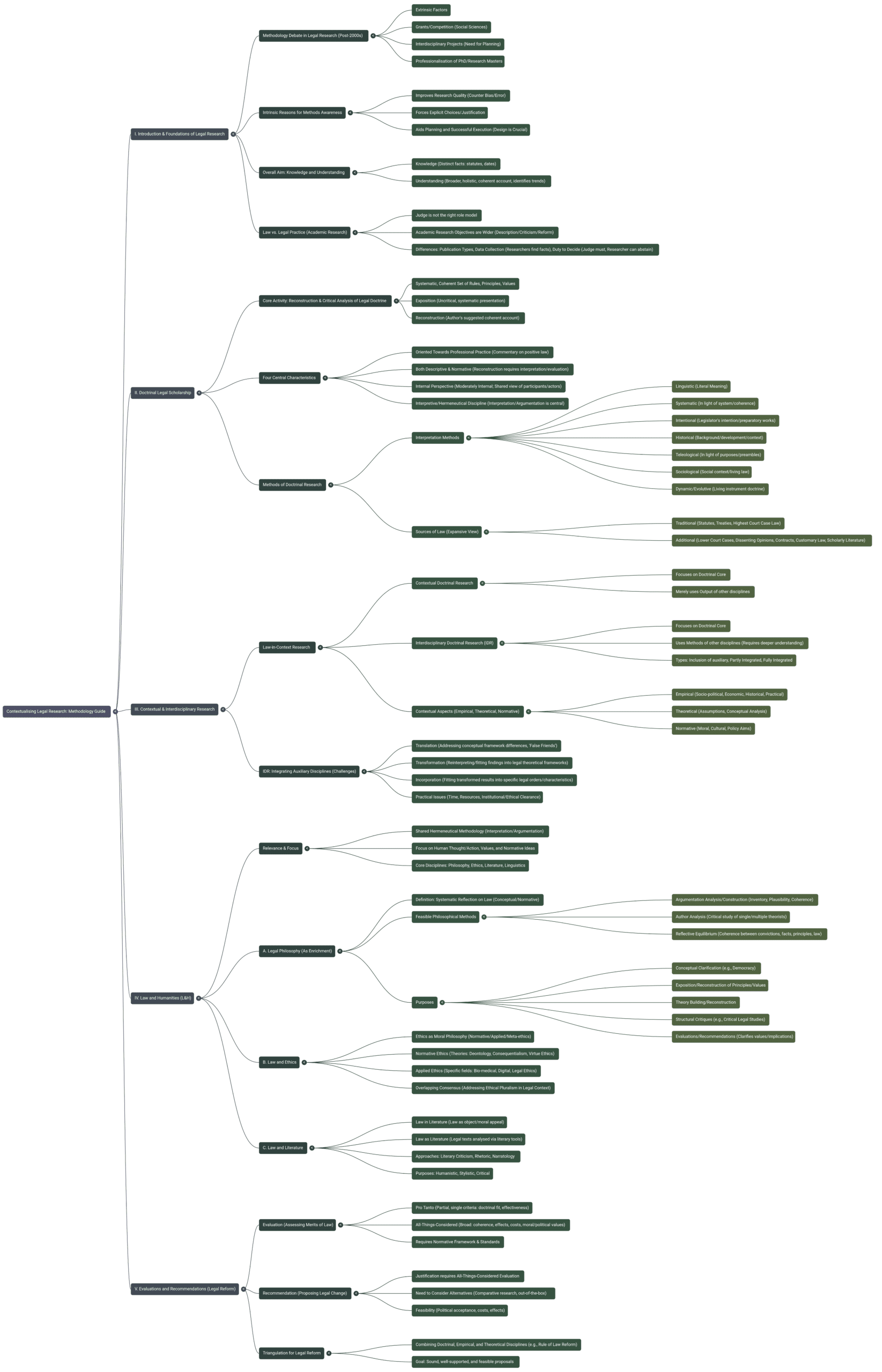

Contextualising Legal Research: A Practical Methods Guide

Doctrinal research is still the backbone of legal scholarship. But if you stop there, you’re often arguing in a vacuum—very polished, very coherent… and sometimes completely detached from what’s actually happening in the world.

That’s the core message behind Contextualising Legal Research: A Methodological Guide: contextualising legal research means keeping doctrinal work as the “core activity,” while strengthening it with empirical input (facts, effects, lived reality) and humanities input (reflection, direction, values, meaning). The authors argue you need both, because without empirical grounding doctrinal work can drift into guesswork, and without humanities-style reflection it can lose purpose and moral clarity.

🔎 Why contextualising legal research matters now

Legal education used to treat “methods” like something social scientists worry about. Law students learned how to find cases and interpret statutes, but they rarely got a structured toolkit for designing research.

That’s changed fast. Since the early 2000s, legal academia has faced pressure to explain and justify methodology—partly because funding bodies like big, interdisciplinary projects, and partly because the best legal research now competes in a world where evidence, impacts, and real-world outcomes matter.

Even more importantly, methodology isn’t bureaucracy. It’s quality control. When you take methods seriously, you’re more likely to:

- spot hidden assumptions,

- reduce bias,

- plan a thesis that actually works,

- and produce results people can follow and trust.

📚 What the foundational text sets out to do

The book is written for legal researchers who see doctrinal research as their base, but want to broaden the scope of what they can do with it—especially in theses and dissertation projects.

In plain language, the goal is to help you:

- keep doctrinal analysis as the “engine,”

- add context without turning your project into a messy Frankenstein,

- and justify your methodological choices so readers understand why you picked your approach.

The authors (Sanne Taekema and Wibren van der Burg) explicitly frame this as law-in-context research design, where doctrinal work is enriched rather than replaced.

🧠 Contextual doctrinal vs interdisciplinary doctrinal research

The book draws a clean line between two types of contextual engagement:

- Contextual doctrinal research: you use the outputs of other disciplines (stats, studies, historical accounts, philosophical arguments), but your method stays mostly doctrinal.

- Interdisciplinary doctrinal research (IDR): you incorporate the theories and methods of other disciplines into your project, not just their conclusions.

Here’s the practical difference: contextual doctrinal research is usually safer and simpler. Interdisciplinary doctrinal research is more powerful—but it’s easier to do poorly.

Contextualising legal research

| Approach | What you add | What stays “core” | Typical risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual doctrinal | Findings from other disciplines (outputs) | Doctrinal interpretation + reconstruction | Cherry-picking evidence that “supports” your legal view |

| Interdisciplinary doctrinal (IDR) | Theories + methods from other disciplines | Still doctrinal, but method becomes hybrid | Misusing the other discipline’s tools (“fake empiricism”) |

🧱 Foundations of doctrinal research

Doctrinal scholarship (in the narrow sense) focuses on understanding how legal parts fit together.

Its core task is the reconstruction and critical analysis of legal doctrine—meaning the coherent set of rules, principles, values, and concepts tied to a topic (like negligence, Charter remedies, or employment misclassification).

Doctrinal research aims for two layers of knowledge:

- knowing the legal materials (“what’s there”),

- and understanding how they form a system (“how it works together”).

⚖️ The distinct character of doctrinal scholarship

The book highlights four features that make doctrinal research its own kind of scholarship.

🧑⚖️ Orientation toward professional practice

Doctrinal research historically speaks to judges, lawyers, and legal institutions. That’s why it often emphasizes positive law and practical coherence.

Even though modern academia pushes more specialization and interdisciplinarity, doctrinal work stays practically relevant because legal systems still run on doctrine.

🧾 Dual descriptive + normative character

Doctrinal work describes law, but interpretation forces choices. The moment you choose one interpretation over another, you’re doing something normative.

Many projects go further by evaluating doctrine and recommending reforms—often because the researcher finds gaps, contradictions, or unfair results.

🔍 Internal perspective (relative autonomy)

Doctrinal researchers often reason from an “internal” legal perspective—similar to how courts justify decisions (coherence, certainty, rule of law).

But the authors support a moderately internal view: keep your legal perspective, while still incorporating knowledge from other disciplines where it genuinely helps.

📜 Humanities-style method (hermeneutics + argument)

Doctrinal work is hermeneutical and argumentative. You interpret authoritative texts, you justify your reading, and you build a coherent account that others can follow.

That “followable” point matters: legal disputes rarely end in perfect closure. So quality is judged by how sound and convincing your reasoning is, not whether someone can replicate your results like a chemistry experiment.

🧭 Objectives: what doctrinal research tries to know and do

The foundational objectives of doctrinal research include:

- Reconstruction: collect legal materials and systematize them; identify gaps and inconsistencies.

- Comparison: compare jurisdictions or legal fields to deepen understanding, improve harmonisation, or identify best practices (often with contextual elements).

- Explanation: ask why the law is shaped the way it is—usually requiring history, politics, or philosophy.

- Evaluation + recommendation: assess quality and propose improvements, using internal doctrinal standards and often external standards too.

A hard truth: the more your project aims at law reform, the more likely you’ll need contextualising legal research. Reform claims without real-world or value-based support are easy to dismiss.

🛠️ Core methods: collecting, interpreting, reconstructing

📚 Collecting research materials

Traditional sources (statutes, treaties, top appellate cases) are only the starting point. In law-in-context work, you may also need:

- lower court rulings,

- administrative policies and guidelines,

- contracts and standard forms,

- dissenting opinions,

- and evidence of informal practices.

🧩 Interpreting texts

Interpretation gives meaning and connects materials into a coherent whole. Common approaches include:

- linguistic,

- systematic,

- intentional,

- historical,

- teleological (purpose-based).

Contextualising legal research often leans on “living” approaches too—like reading law in today’s social conditions (sociological interpretation) or using dynamic interpretation when the legal instrument is designed to evolve.

🧱 Reconstructing doctrine

Reconstruction means building the best coherent account that fits legal materials and basic principles. Scholars can (and should) openly find incoherence—unlike judges, who must reach a decision even if the law is messy.

🧩 Theoretical and normative frameworks that keep you honest

A framework isn’t the same as a literature review. It’s the lens that:

- defines concepts,

- positions your work in scholarship,

- and justifies your research question and evaluation standards.

Two major types:

- Explanatory frameworks: help explain a phenomenon (example: using principal–agent theory to analyze corporate governance).

- Normative frameworks: provide standards (justice, fairness, efficiency, dignity, coherence). They can be:

- internal (derived from legal principles like rule of law),

- external (drawn from political philosophy, economics, ethics).

Key rule: if you make normative claims, say your standards out loud and defend them. The “law itself” usually isn’t a good enough hidden framework, especially when you’re doing contextualising legal research and recommending change.

🌍 Law-in-context: what “context” really means

“Law-in-context” is the umbrella idea for projects that go beyond mono-disciplinary doctrine while keeping a doctrinal core.

The book describes context in three broad dimensions:

- Empirical: history, politics, economics, social realities.

- Theoretical: assumptions and concepts behind doctrine.

- Normative: moral, cultural, and policy background.

A useful way to think about it: context is the difference between “law on the page” and “law as it behaves.” That’s why empirical legal studies keep showing up in modern methods conversations.

🤝 The interdisciplinary spectrum: from add-on to full merge

Interdisciplinary doctrinal research (IDR) uses an auxiliary discipline to enrich a doctrinal project.

Common pairings:

- law + social sciences (economics, sociology, criminology) for realism,

- law + humanities (philosophy, ethics, literature) for meaning and values.

Integration can be light or intense: Contextualising legal research

| Level | What it looks like | Best for |

|---|---|---|

| Auxiliary inclusion | A doctrinal project with a non-doctrinal sub-study | Theses that need one “reality check” (e.g., a small dataset) |

| Partly integrated | Two disciplinary tracks that interact and adjust | Team projects; mixed-method dissertations |

| Fully integrated | One merged project with an integrative question | Broad law reform proposals; institutional redesign |

The stronger the integration, the more you must understand the other discipline properly—otherwise you risk producing confident nonsense.

🧯 Integration challenges: translation, transformation, incorporation

Because disciplines differ in concepts, goals, and standards, the book emphasizes three key steps when integrating non-legal material into doctrine.

🗣️ Translation

Words don’t travel well. “Responsibility” in philosophy, sociology, and law can mean wildly different things. You must learn the auxiliary discipline’s dialect so you don’t fall for “semantic false friends.”

🔁 Transformation

You don’t paste empirical findings straight into law. You select, interpret, and reshape them to fit your doctrinal framework and the legal question.

Example: a study about policing outcomes might become part of a proportionality analysis or an access-to-justice critique, rather than being treated as “the answer.”

🧩 Incorporation

Legal systems have their own structure and values: procedural safeguards, legality, rule of law, institutional roles. Non-legal insights must be adapted to that reality, not dumped on top of it.

🧮 Evaluation and recommendations: making normative claims defensible

Once you move into evaluation and law reform, the methodological bar goes up.

The book frames good evaluation as a structured process:

- Pick evaluation standards (justice, efficiency, coherence) and justify them.

- Operationalize the values into criteria you can actually assess.

- Do a broad assessment (ideally all-things-considered): doctrinal coherence, empirical effects/costs, and theoretical-normative justification.

- Balance conflicting “pro tanto” evaluations (partial wins) into a final justified conclusion.

Recommendations also need comparison:

- compare your proposal to the status quo,

- compare it to reasonable alternatives,

- and consider feasibility (political and institutional).

This is where contextualising legal research really earns its keep: it stops your “recommendations” from being just vibes with footnotes.

🏛️ Law and the humanities: philosophy, ethics, literature

The book treats humanities not as decoration, but as core support for doctrinal work—because law is soaked in language, values, and persuasion.

🧠 Legal philosophy

Three methods doctrinal scholars can realistically use:

- 🧩 Argument mapping + construction: lay out arguments pro/con and strengthen transparency.

- 📚 Author analysis: critically use strong thinkers (keep what works; reject what doesn’t).

- ⚖️ Reflective equilibrium: test cases, principles, facts, and legal commitments against each other until your account becomes more coherent and robust.

🧭 Ethics (moral philosophy)

Ethics is essential when law regulates moral issues (bioethics, end-of-life decisions, taxation fairness). But pluralism is real: societies disagree.

So ethical input often aims at:

- identifying overlapping consensus,

- or clearly presenting competing arguments so lawmakers can decide transparently.

📖 Law and literature

Two big modes:

- 📚 Law in literature: literature helps explore the human experience behind legal rules (empathy, imagination, moral insight).

- 📝 Law as literature: treat judicial reasons as crafted narratives—use rhetoric and narratology to analyze persuasion, framing, and assumptions.

Humanities-based methods also reinforce the hermeneutics point: interpretation is never purely mechanical, and awareness of that fact improves research honesty.

🔺 Triangulation: doctrinal + empirical + normative

The book’s closing push is what I’d call a “triple-check” mindset: triangulation of perspectives.

Instead of relying on one lens, you combine:

- Doctrinal research (system, coherence, interpretation).

- Empirical research (effects, costs, acceptance, how law functions).

- Theoretical-normative research (values, justification, direction).

When you triangulate, you compensate for each method’s blind spots. That’s especially important in law reform projects, where bad reforms often fail because they were either unrealistic, unjustified, or doctrinally incoherent.

❓ FAQs – Contextualising legal research

❓ What is contextualising legal research?

It’s doctrinal research strengthened by context—especially empirical facts and humanities-based reflection—so the legal analysis stays coherent and real-world grounded.

❓ What’s the difference between contextual doctrinal research and interdisciplinary doctrinal research?

Contextual doctrinal research uses other disciplines’ findings. Interdisciplinary doctrinal research also uses their theories and methods inside the legal project.

❓ Is doctrinal research only “black-letter law”?

It’s often described that way because it focuses on legal texts. But doctrinal work can also include critique, theory, and reform—especially when you contextualise it.

❓ Why do legal researchers need empirical methods?

Because doctrinal coherence doesn’t prove real-world effects. Empirical work helps test how law functions in practice (costs, outcomes, acceptance).

❓ What is “hermeneutics” and why does it matter in law?

Hermeneutics studies interpretation. In law, it matters because meaning depends on text, context, and the interpreter—so better research makes that process transparent and defensible.

❓ What does a “moderately internal” perspective mean?

It means reasoning from legal standards like courts do, while still using outside knowledge when it improves accuracy and justification.

❓ When should I use a normative framework?

Any time you evaluate law or recommend change. You need explicit values and criteria (justice, efficiency, fairness), not hidden assumptions.

❓ What are the biggest risks in interdisciplinary legal research?

Misusing concepts (translation errors), forcing findings into law without adaptation (transformation errors), and ignoring legal-system constraints (incorporation errors).

❓ How do I make a law reform recommendation more credible?

Compare options, justify standards, test empirical impacts, and balance competing values instead of arguing only from doctrine.

❓ What is triangulation in legal research?

It’s combining doctrinal, empirical, and theoretical-normative perspectives so each one checks the others’ blind spots.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions: Contextualising Legal Research: A Methodological Guide

This FAQ addresses the core themes, methods, and arguments presented in Contextualising Legal Research: A Methodological Guide by Sanne Taekema and Wibren van der Burg.

🧱 I. The Book’s Foundation and Scope

Q1: What is the primary purpose and scope of Contextualising Legal Research: A Methodological Guide?

The primary aim of the book is to provide a practical and reflective discussion of research methods for legal researchers who view doctrinal research as their core activity but seek to broaden their research scope. The authors believe that doctrinal research can and should be enriched by other disciplines, including both empirical studies and the humanities. This methodology guide specifically aims to fill a gap in existing literature, which often focuses solely on doctrinal research or empirical legal studies, by providing direction for students at master’s and PhD levels on how to conduct law-in-context research,.

Q2: Why has attention to legal research methodology become increasingly important in recent years?

The increased focus on legal research methods is driven by both extrinsic and intrinsic factors:

- Extrinsic Factors: Law needs to compete for research grants alongside social sciences, necessitating more rigorous articulation of research methods. Furthermore, research is increasingly executed in larger, often interdisciplinary, projects, requiring careful methodological planning and discussion among researchers from different disciplines. The professionalisation of PhD training and the emergence of research masters also created demand for adequate methodological materials.

- Intrinsic Factors: Awareness of methodology improves research quality by helping researchers uncover assumptions and counter bias. Methodological awareness is also crucial for efficiently planning and executing research projects, especially theses, preventing delays and insufficient focus.

⚖️ II. Doctrinal Research: Characteristics and Methods

Q3: What is doctrinal research, and what are its four main characteristics?

Doctrinal scholarship (legal scholarship in the narrow sense) focuses on understanding the systematic relationship between legal elements. Its core activity is the reconstruction and critical analysis of legal doctrine.

Doctrinal scholarship is characterized by:

- Orientation Towards Professional Practice: It is closely allied with the legal professions (judges, lawyers, notaries) because law schools educate students for these careers,.

- Dual Descriptive and Normative Character: It aims to systematically reconstruct existing positive law (descriptive), but interpretation involves normative choices, often leading to evaluation and recommendations for law reform,.

- An Internal Perspective (Relative Autonomy): Scholars adopt the viewpoint of participants in the practice of law. This perspective involves acknowledging and utilizing internal legal standards such as coherence, legal certainty, and the rule of law. The authors advocate a moderately internal point of view which maintains the legal perspective while incorporating external knowledge.

- Methods of the Humanities (Hermeneutics): It is fundamentally an hermeneutical and argumentative enterprise centered on the authoritative interpretation of texts,,.

Q4: How does academic doctrinal research fundamentally differ from the role of a judge?

The primary differences relate to purpose, methodology, and conclusion: Contextualising legal research

| Aspect | Judge’s Role | Academic Researcher’s Role |

|---|---|---|

| Research Problem | Must focus on the problem/case defined by the parties in court. | Is free to choose the research problem, scope, depth, and methods. |

| Data/Facts | Is often limited to the facts presented by the parties. | Must find the relevant facts, including general empirical theories (e.g., psychological or economic). |

| Coherence/Conclusion | Has a duty to decide and must construct the law as a coherent system that justifies the decision,. | Can abstain from judgment if arguments are inconclusive. Must be open to finding that the law is fragmented, containing gaps and inconsistencies,. |

| Standard | Seeks conclusions judged by the standard of authority or sound justification. | Seeks conclusions judged by their soundness and convincingness,. Results must be “retraceable” or “followable,” not necessarily replicable. |

Q5: What are the main objectives of doctrinal research?

While the core objective is the systematic reconstruction of a legal order as a more or less coherent doctrine,, other primary objectives include,,:

- Comparison: Comparing laws across various jurisdictions or fields, often to gain knowledge, better understand one’s own system, or identify best practices for harmonization,.

- Explanation: Asking why law is the way it is, which usually requires non-legal insights (historical, political, or philosophical).

- Evaluation and Recommendation: Assessing the quality of law and suggesting improvements, often requiring interdisciplinary input based on external normative standards,.

🌐 III. Contextual and Interdisciplinary Research

Q6: What is the difference between contextual doctrinal research and interdisciplinary doctrinal research?

Law-in-context research encompasses all projects that go beyond monodisciplinary doctrine while retaining a doctrinal core,. Within this field, two types are distinguished,:

- Contextual Doctrinal Research: Research focused on a doctrinal core that merely includes the output (insights and data) of other disciplines. Researchers rely on authoritative sources from auxiliary disciplines (e.g., using statistics from criminology),.

- Interdisciplinary Doctrinal Research (IDR): Research focused on a doctrinal core that includes the theories and methods of other disciplines. This type requires the researcher to have a more thorough understanding and possibly mastery of the auxiliary discipline,,.

Q7: What are the three crucial activities required for integrating the findings of auxiliary disciplines into a doctrinal research project?

Due to conceptual and methodological differences between disciplines, integration is necessary via,:

- Translation: Addressing terminological differences and conflicting conceptual frameworks (e.g., avoiding “semantic false friends” where the same word has different meanings across disciplines, like “institution” or “responsibility”),.

- Transformation: Selecting, reinterpreting, and adapting the non-doctrinal findings to ensure they are useful and relevant for the specific doctrinal theoretical framework, methods, objectives, and problem awareness of the main project,.

- Incorporation: Taking into account the distinct characteristics of the specific legal order (such as its rule-oriented structure, dual political/normative nature, procedural safeguards, and fundamental values like legality) when translating non-legal insights,.

Q8: What role do theoretical and normative frameworks play in a research project?

A theoretical framework—the theory or set of theories guiding the research—is essential for situating the project, defining core concepts, and justifying the research question,.

- Explanatory Frameworks: Provide an account of a phenomenon, aiding reconstruction and understanding (e.g., principal-agent theory in company law),.

- Normative Frameworks: Provide standards and values used as criteria for evaluation and recommendation,,,. These frameworks can be internal (derived from existing legal principles and values) or external (derived from external theories like political philosophy or economics),.

📚 IV. Interdisciplinary Humanities Methods

Q9: Why are the humanities considered vital for legal research?

Doctrinal research is inherently hermeneutic, sharing methods with the humanities,. The humanities are vital because they offer a reflective understanding of law. Without the input of the humanities, doctrinal research lacks reflection and direction. They are crucial for,:

- Cultural and Normative Understanding: Providing insight into historical, cultural, and moral backgrounds of law.

- Critical Reflection: Providing theoretical arguments to uncover and examine presuppositions underlying legal thinking (e.g., using critical legal studies),,.

- Creativity and Imagination: Stimulating new ways of approaching problems, often drawing from art and literature,.

Q10: What philosophical methods are considered relevant and feasible for doctrinal researchers to employ?

Legal philosophy is continuous with methods used in doctrinal research, making it relatively feasible for lawyers without extensive philosophical training. Key methods include:

- Argumentation Analysis and Construction: Mapping, analyzing, and constructing arguments (both pro and contra) concerning a legal position to improve the soundness and transparency of legal reasoning,.

- Author Analysis: Critically engaging with the theories of influential philosophers, selecting plausible and well-argued elements,.

- Reflective Equilibrium: A coherence method that involves collecting and testing all plausible convictions—concrete cases, general principles, empirical facts, and legal insights—against each other until a coherent and robust theoretical account is constructed,,.

Q11: What are the principal differences in approach between the Law and Literature sub-disciplines?

Law and literature is generally divided into two main strands,:

- Law in Literature: Uses novels and other literary works to explore the human context of law, emphasizing themes like empathy, imagination, and moral predicaments. This strand often highlights the limitations of purely legal methods and serves a humanistic purpose,.

- Law as Literature: Analyzes legal texts (e.g., statutes, judicial opinions) using the tools of literary criticism, rhetoric (the art of persuasion), and narratology (the study of narrative structure),,. This serves a stylistic purpose by focusing on how law’s language operates as a power form.

🧠 V. Normative Research, Evaluation, and Triangulation

Q12: How can sound evaluations and recommendations for legal reform be methodologically justified?

Justifying evaluations and recommendations is highly demanding, often requiring an interdisciplinary approach,. A sound argument for an evaluation requires,:

- Explicit Argumentation: Every step in the argument must be spelled out and justified, acknowledging counterarguments and the provisional, defeasible nature of normative conclusions,.

- Evaluation Standards: The research must identify and justify its evaluation standards, which refer directly or indirectly to fundamental values (e.g., justice, coherence, efficiency),.

- Broad Assessment: Ideally, an all-things-considered evaluation is conducted, assessing the subject against all relevant legal, empirical, and theoretical-normative standards,.

Recommendations require an additional comparative element: comparing the proposed solution not only to the status quo but also to all reasonable alternatives, assessing the pros and cons against all relevant standards,.

Q13: What is the concept of “triangulation of perspectives” and why is it crucial for rigorous legal research?

Triangulation, adapted from social science methodology, means combining disciplinary approaches to gain a more complete and methodologically sound assessment,. For projects focused on law reform, it requires combining three distinct perspectives,,:

- Legal Doctrinal Research: Provides systematic reconstruction and analysis based on legal texts (the coherence check).

- Empirical Research: Provides data on how law functions in society, including effects and costs (the realism check).

- Theoretical-Normative Research: Provides clarification of fundamental values and develops normative frameworks (the reflection check).

Each perspective has inherent limitations (e.g., doctrinal research suffers from path-dependency; purely theoretical work may lack feasibility), and triangulation compensates for these weaknesses,. This integration is vital for moving beyond restricted, partial (pro tanto) conclusions to justified, comprehensive (all-things-considered) recommendations,.

✅ Conclusion: turning methodology into a research plan

If you remember one thing, make it this: contextualising legal research doesn’t weaken doctrinal work—it upgrades it. It keeps your legal analysis coherent, but it also forces you to confront evidence, impacts, and values with your eyes open.

So here’s the practical move: when you design your next thesis or article, write a one-paragraph “method pledge” to yourself:

- What is my doctrinal core?

- What context do I need (empirical, theoretical, normative)?

- Which framework will I use to justify evaluation?

- How will I make my reasoning followable?

Sources & References – Contextualising legal research

- Edward Elgar Publishing — Contextualising Legal Research (Edward Elgar Publishing)

- Google Books — Contextualising Legal Research: A Methodological Guide (Google Books)

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy — “Legal Hermeneutics” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- SSRN (Tom R. Tyler) — “Methodology in Legal Research” (SSRN)

- AU Press — Legal Literacy (internal vs external perspectives; doctrinal research) (AU Press)

Related Videos:

Related Posts:

Coase Social Cost: 17 Practical Insights for Law + Econ

Spur Industries v Del E Webb: Indemnity and Urban Growth

Rawls Theory of Justice Explained: Justice as Fairness

Modern AI Concepts Explained: 5 Pillars Shaping Our Future

Admin Network Security in the Cloud-Native Era: Tools, Tactics & Real-World Defenses