- Home

- Blog

- Downloads

- Forum

- Games

- FAQs

- News

- Events

- Shop

- Code

- Contact

About Us

Have questions? Reach out to us anytime through our Contact page.

Read our Privacy Policy, Legal Disclaimer, and Site Content Policy to understand how we protect your data, your rights, and the rules for using our site.

Schedule a meeting with us at your convenience.

Book a meeting with Bernard Aybout

Our Products & Services

Explore our full range of products and services designed to meet your needs.

Get fast, reliable support from our helpdesk team—here when you need us.

Enter Virii8Social — your space to build, connect, and bring communities to life.

Stream live TV. Watch on demand. Record while you watch.

An all-in-one app for unit conversions, scientific math, financial tools, and advanced calculations—seamlessly in one place.

a secure routing platform that sequentially collects signatures on Word or PDF documents with an automated, legally-certified audit trail.

JBD After Hour Notary – Reliable notary services, available when others aren’t.

Priority-coded lists, Kanban board, voice dictation, and search/sort functionality.

An autonomous driving car with sentinel-like abilities uses a constantly vigilant, multi-sensor AI system that not only navigates and avoids hazards but also actively anticipates threats, protects occupants, and adapts in real time to maintain maximum safety and situational awareness.

- Health

- About Us

- Login

- Register

Approx. read time: 41.1 min.

Post: Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Checkers, also known as draughts in some countries, is a classic board game played by two people. The game takes place on an 8×8 square board with alternating dark and light squares, but only the dark squares are used. Each player starts with 12 pieces placed on the three closest rows to them, on the dark squares. The objective of the game is to capture all of the opponent’s pieces or block them so they cannot make a move.

Basic Rules:

-

Movement: Players take turns moving one of their pieces. Pieces move diagonally forward one square to an empty square.

-

Captures: If an opponent’s piece is diagonally in front of a player’s piece and the square beyond it is empty, the player’s piece can “jump” over the opponent’s piece, capturing it. The captured piece is removed from the board. If a player can make a capture, they must do so.

-

Multiple Jumps: If, after making a jump, a piece is in a position to make another jump (either because it landed next to another opponent’s piece with a space behind it or a series of such positions), it must continue to do so. This can result in multiple captures in a single turn.

-

Kinging: When a piece reaches the farthest row from the player who controls that piece, it is “kinged” and becomes a King. Kings can move diagonally forward or backward, giving them more mobility than a regular piece. Usually, a kinged piece is marked by placing another piece on top of it.

-

Winning the Game: The game is won by either capturing all of the opponent’s pieces or putting them into a position where they cannot move. A game can also end in a draw if neither side can force a win.

Advanced Rules/Variances:

-

Forced Capture: Most versions of checkers require that if you can make a capture, you must make a capture. In some variations, if multiple capture moves are available, the player may choose which to perform, not necessarily the one that captures the most pieces.

-

Flying Kings: In some variants, kings are given the ability to move across multiple empty squares in one direction, known as “flying kings”.

-

Opening: The game’s strategy can significantly vary from the beginning (opening), through the middle (middlegame), to the end (endgame). Strategic placement and movement are key.

Checkers is a game of strategic thinking, planning, and foresight, with simple rules that lead to complex tactical situations. The game’s simplicity makes it accessible to beginners, but it also offers depth for experienced players to explore.

Scoreboard

Player 1 (Black) Captures: 0, Kings: 0

Player 2 (Red) Captures: 0, Kings: 0

English draughts

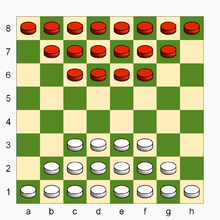

A standard American Checker Federation (ACF) set: smooth red and white 1.25-inch (32 mm) diameter pieces; green and buff 2-inch (51 mm) squares

|

|

| Genres |

|

|---|---|

| Players | 2 |

| Playing time | Casual games usually last 10 to 30 minutes |

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonyms |

|

English draughts (British English) or checkers (American English), also called straight checkers or simply draughts, is a form of the strategy board game checkers (or draughts). It is played on an 8×8 checkerboard with 12 pieces per side. The pieces move and capture diagonally forward, until they reach the opposite end of the board, when they are crowned and can thereafter move and capture both backward and forward.

As in all forms of draughts, English draughts is played by two opponents, alternating turns on opposite sides of the board. The pieces are traditionally black, red, or white. Enemy pieces are captured by jumping over them.

The 8×8 variant of draughts was weakly solved in 2007 by a team of Canadian computer scientists led by Jonathan Schaeffer. From the standard starting position, both players can guarantee a draw with perfect play.

Pieces – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Though pieces are traditionally made of wood, now many are made of plastic, though other materials may be used. Pieces are typically flat and cylindrical. They are invariably split into one darker and one lighter colour. Traditionally and in tournaments, these colours are red and white, but black and red are common in the United States, as well as dark- and light-stained wooden pieces. The darker-coloured side is commonly referred to as “Black”; the lighter-coloured side, “White”.

There are two classes of pieces: men and kings. Men are single pieces. Kings consist of two men of the same colour, stacked one on top of the other. The bottom piece is referred to as crowned. Some sets have pieces with a crown molded, engraved or painted on one side, allowing the player to simply turn the piece over or to place the crown-side up on the crowned man, further differentiating kings from men. Pieces are often manufactured with indentations to aid stacking.

Rules

Starting position

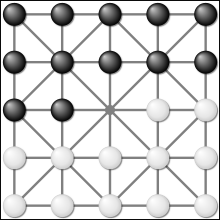

Each player starts with 12 men on the dark squares of the three rows closest to that player’s side (see diagram). The row closest to each player is called the kings row or crownhead. The player with the darker-coloured pieces moves first. Then turns alternate.

Move rules – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

There are two different ways to move in English draughts:

- Simple move: A simple move consists of moving a piece one square diagonally to an adjacent unoccupied dark square. Uncrowned pieces can move diagonally forward only; kings can move in any diagonal direction.

- Jump: A jump consists of moving a piece that is diagonally adjacent an opponent’s piece, to an empty square immediately beyond it in the same direction (thus “jumping over” the opponent’s piece front and back ). Men can jump diagonally forward only; kings can jump in any diagonal direction. A jumped piece is considered “captured” and removed from the game. Any piece, king or man, can jump a king.

Jumping is always mandatory: if a player has the option to jump, they must take it, even if doing so results in disadvantage for the jumping player. For example, a mandated single jump might set up the player such that the opponent has a multi-jump in reply.

Multiple jumps are possible, if after one jump, another piece is immediately eligible to be jumped by the moved piece—even if that jump is in a different diagonal direction. If more than one multi-jump is available, the player can choose which piece to jump with, and which sequence of jumps to make. The sequence chosen is not required to be the one that maximizes the number of jumps in the turn; however, a player must make all available jumps in the sequence chosen.

Kings

If a man moves into the kings row on the opponent’s side of the board, it is crowned as a king and gains the ability to move both forward and backward. If a man moves into the kings row or if it jumps into the kings row, the current move terminates; the piece is crowned as a king but cannot jump back out as in a multi-jump until the next move.

End of game

A player wins by capturing all of the opponent’s pieces or by leaving the opponent with no legal move. The game is a draw if neither side can force a win, or by agreement (one side offering a draw, the other accepting).

Shortest possible game

The December 1977 issue of the English Draughts Association Journal published a letter from Alan Beckerson of London who had discovered a number of complete games of twenty moves in length. These were the shortest games ever discovered and gained Alan a place in the Guinness Book of Records. He offered a £100 prize to anybody who could discover a complete game in less than twenty moves. In February 2003, Martin Bryant (author of the Colossus draughts program) published a paper on his website[1] presenting an exhaustive analysis showing that there exist 247 games of twenty moves in length (and confirmed that this is the shortest possible game) leading (by tranposition) to 32 distinct final positions.

Rule variations

- In tournament English draughts, a variation called three-move restriction is preferred. The first three moves are drawn at random from a set of accepted openings. Two games are played with the chosen opening, each player having a turn at either side. This tends to reduce the number of draws and can make for more exciting matches. Three-move restriction has been played in the U.S. championship since 1934. A two-move restriction was used from 1900 until 1934 in the United States and in the British Isles until the 1950s. Before 1900, championships were played without restriction, a style is called Go As You Please (GAYP).

- One rule which has fallen out of favor is the huffing rule. In this variation jumping is not mandatory, but if a player does not make a jumping move when there is one available to them (either deliberately or by failing to see it), the opponent may declare that the piece that could have made the jump is blown or huffed, i.e. removed from the board. After huffing the offending piece, the opponent then takes their turn as normal.[2] Huffing does not appear in the official rules of the World Checkers Draughts Federation, of which the American Checker Federation and English Draughts Association are members.[3][4]

- Two common rule variants, not recognised by player associations, are:

- Capturing with a king precedes capturing with a man. In this case, any available capture can be made at the player’s choice.

- A man that has jumped to become a king can then in the same turn continue to capture other pieces in a multi-jump.

Notation

There is a standardised notation for recording games. All 32 reachable board squares are numbered in sequence. The numbering starts in Black’s double-corner (where Black has two adjacent squares). Black’s squares on the first rank are numbered 1 to 4; the next rank 5 to 8, and so on. Moves are recorded as “from-to”, so a move from 9 to 14 would be recorded 9-14. Captures are notated with an “x” connecting the start and end squares. The game result is often abbreviated as BW/RW (Black/Red wins) or WW (White wins).

Sample game

White resigned after Black’s 46th move.

- [Event “1981 World Championship Match, Game #37”] [Black “M. Tinsley”] [White “A. Long”] [Result “1–0”] 1. 9-14 23-18 2. 14×23 27×18 3. 5-9 26-23 4. 12-16 30-26 5. 16-19 24×15 6. 10×19 23×16 7. 11×20 22-17 8. 7-11 18-15 9. 11×18 28-24 10. 20×27 32×5 11. 8-11 26-23 12. 4-8 25-22 13. 11-15 17-13 14. 8-11 21-17 15. 11-16 23-18 16. 15-19 17-14 17. 19-24 14-10 18. 6×15 18×11 19. 24-28 22-17 20. 28-32 17-14 21. 32-28 31-27 22. 16-19 27-24 23. 19-23 24-20 24. 23-26 29-25 25. 26-30 25-21 26. 30-26 14-9 27. 26-23 20-16 28. 23-18 16-12 29. 18-14 11-8 30. 28-24 8-4 31. 24-19 4-8 32. 19-16 9-6 33. 1×10 5-1 34. 10-15 1-6 35. 2×9 13×6 36. 16-11 8-4 37. 15-18 6-1 38. 18-22 1-6 39. 22-26 6-1 40. 26-30 1-6 41. 30-26 6-1 42. 26-22 1-6 43. 22-18 6-1 44. 14-9 1-5 45. 9-6 21-17 46. 18-22 BW

Unicode

In Unicode, the draughts are encoded in block Miscellaneous Symbols:

- U+26C0 ⛀ WHITE DRAUGHTS MAN

- U+26C1 ⛁ WHITE DRAUGHTS KING

- U+26C2 ⛂ BLACK DRAUGHTS MAN

- U+26C3 ⛃ BLACK DRAUGHTS KING

Sport

The men’s World Championship in English draughts dates to the 1840s, predating the men’s Draughts World Championship, the championship for men in International draughts, by several decades. Noted world champions include Andrew Anderson, James Wyllie, Robert Martins, Robert D. Yates, James Ferrie, Alfred Jordan, Newell W. Banks, Robert Stewart, Asa Long, Walter Hellman, Marion Tinsley, Derek Oldbury, Ron King, Michele Borghetti, Alex Moiseyev, Lubablo Kondlo,[5] Sergio Scarpetta, Patricia Breen, and Amangul Durdyyeva.[6] Championships are held in GAYP (Go As You Please) and 3-Move versions.

From 1840 to 1994, the men’s winners were from Scotland, England, and the United States. From 1994 to 2023, the men’s winners were from the United States, Barbados, South Africa and Italy.

The woman’s championship started in 1993. As of 2022, the women’s winners have been from Ireland, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine.

The European Cup has been held since 2013; the World Cup, since 2015.

Computer players

The first English draughts computer program was written by Christopher Strachey, M.A. at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), London.[7] Strachey finished the programme, written in his spare time, in February 1951. It ran for the first time on the NPL’s Pilot ACE computer on 30 July 1951. He soon modified the programme to run on the Manchester Mark 1 computer.

The second computer program was written in 1956 by Arthur Samuel, a researcher from IBM. Other than it being one of the most complicated game playing programs written at the time, it is also well known for being one of the first adaptive programs. It learned by playing games against modified versions of itself, with the victorious versions surviving. Samuel’s program was far from mastering the game, although one win against a blind checkers master gave the general public the impression that it was very good.

In November 1983, the Science Museum Oklahoma (then called the Omniplex) unveiled a new exhibit: Lefty the Checker Playing Robot. Programmed by Scott M Savage, Lefty used an Armdroid robotic arm by Colne Robotics and was powered by a 6502 processor with a combination of BASIC and Assembly code to interactively play a round of checkers with visitors. Originally, the program was deliberately simple so that the average visitor could potentially win, but over time was improved. The improvements proved to be frustrating for the visitors, so the original code was reimplemented.[8]

In the 1990s, the strongest program was Chinook, written in 1989 by a team from the University of Alberta led by Jonathan Schaeffer. Marion Tinsley, world champion from 1955–1962 and from 1975–1991, won a match against the machine in 1992. In 1994, Tinsley had to resign in the middle of an even match for health reasons; he died shortly thereafter. In 1995, Chinook defended its man-machine title against Don Lafferty in a thirty-two game match. The final score was 1–0 with 31 draws for Chinook over Don Lafferty.[9] In 1996 Chinook won in the U.S. National Tournament by the widest margin ever, and was retired from play after that event. The man-machine title has not been contested since.

In July 2007, in an article published in Science Magazine, Chinook’s developers announced that the program had been improved to the point where it could not lose a game.[10] If no mistakes were made by either player, the game would always end in a draw. After eighteen years, they have computationally proven a weak solution to the game of checkers.[11] Using between two hundred desktop computers at the peak of the project and around fifty later on, the team made 1014 calculations to search from the initial position to a database of positions with at most ten pieces.[12] However, the solution is only for the initial position rather than for all 156 accepted random 3-move openings of tournament play.

Computational complexity

The number of possible positions in English draughts is 500,995,484,682,338,672,639[13] and it has a game-tree complexity of approximately 1040.[14] By comparison, chess is estimated to have between 1043 and 1050 legal positions.

When draughts is generalized so that it can be played on an m×n board, the problem of determining if the first player has a win in a given position is EXPTIME-complete.

The July 2007 announcement by Chinook‘s team stating that the game had been solved must be understood in the sense that, with perfect play on both sides, the game will always finish with a draw. However, not all positions that could result from imperfect play have been analysed.[15]

Some top draughts programs are Chinook, and KingsRow.

See also

Notes

- ^ When this word is used in the UK, it is usually spelt chequers (as in Chinese chequers); see further at American and British spelling differences.

References

- ^ “Colossus Games”. Colossus Games. 9 September 2021.

- ^ Cady, Alice Howard (1896). Checkers: A Treatise on the Game. New York: American Sports Publishing Company. p. 15. ISBN 1340551446.

- ^ “Rules of Draughts (Checkers)”. World Checkers Draughts Federation. 2012.

- ^ “Federation-Members”. World Checkers Draughts Federation. 1 December 2019.

- ^ “PE’s Lubabalo Kondlo crowned world draughts champion”. YouTube.

- ^ WCDF champions list

- ^ The Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery Meeting, Toronto, 1952.

- ^ “But Can It Type”. The Daily Oklahoman. The Daily Oklahoman. 25 November 1983. p. 51. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ “Man vs. Machine World Championship: Petal, Mississippi, January 7–17, 1995”. Chinook.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 19, 2007). “Computer Checkers Program Is Invincible”. The New York Times.

- ^ Schmid, Randolph E (July 19, 2007). “Computer can’t lose checkers”. USA Today.

- ^ “Checkers ‘solved’ after years of number crunching”. New Scientist. July 19, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007.

- ^ “Chinook – Total Number of Positions”. webdocs.cs.ualberta.ca. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- ^ Schaeffer, Jonathan (2007). “Game over: Black to play and draw in checkers”. ICGA Journal. 30 (4): 187–197. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.154.255. doi:10.3233/ICG-2007-30402.

- ^ Schaeffer, Jonathan (14 September 2007). “Checkers Is Solved”. Science. 317 (5844): 1518–1522. Bibcode:2007Sci…317.1518S. doi:10.1126/science.1144079. PMID 17641166. S2CID 10274228.

External links

- World Checkers Draughts Federation (WCDF)

- American Checker Federation (ACF)

- List of world checkers champions

- “Draughts” . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 547–50.

Checker

Starting position for American checkers on an 8×8 checkerboard; Black (red) moves first.

|

|

| Years active | at least 5,000 |

|---|---|

| Genres | |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | <1 minute |

| Playing time | Casual games usually last 10 to 30 minutes; tournament games last anywhere from about 60 minutes to 3 hours or more. |

| Chance | None |

| Age range | 4+ |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonyms |

|

Checkers[note 1] (American English), also known as draughts (/drɑːfts, dræfts/; British English), is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve forward movements of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Checkers is developed from alquerque.[1] The term “checkers” derives from the checkered board which the game is played on, whereas “draughts” derives from the verb “to draw” or “to move”.[2]

The most popular forms of checkers in Anglophone countries are American checkers (also called English draughts), which is played on an 8×8 checkerboard; Russian draughts and Turkish draughts, both on an 8×8 board; and International draughts, played on a 10×10 board – with the latter widely played in many countries worldwide. There are many other variants played on 8×8 boards. Canadian checkers and Singaporean/Malaysian checkers (also locally known as dam)[citation needed] are played on a 12×12 board.

American checkers was weakly solved in 2007 by a team of Canadian computer scientists led by Jonathan Schaeffer. From the standard starting position, perfect play by each side would result in a draw.

General rules – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Checkers is played by two opponents on opposite sides of the game board. One player has dark pieces (usually black); the other has light pieces (usually white or red). White moves first, then players alternate turns. A player cannot move the opponent’s pieces. A move consists of moving a piece forward to an adjacent unoccupied square. If the adjacent square contains an opponent’s piece, and the square immediately beyond it is vacant, the piece may be captured (and removed from the game) by jumping over it.

Only the dark squares of the checkerboard are used. A piece can only move forward into an unoccupied square. When capturing an opponent’s piece is possible, capturing is mandatory in most official rules. If the player does not capture, the other player can remove the opponent’s piece as a penalty (or muffin), and where there are two or more such positions the player forfeits pieces that cannot be moved (although some rule variations make capturing optional). In almost all variants, the player without pieces remaining, or who cannot move due to being blocked, loses the game.

Pieces

Man

An uncrowned piece (man) moves one step ahead and captures an adjacent opponent’s piece by jumping over it and landing on the next square. Multiple enemy pieces can be captured in a single turn provided this is done by successive jumps made by a single piece; the jumps do not need to be in the same line and may “zigzag” (change diagonal direction). In American checkers, men can jump only forwards; in international draughts and Russian draughts, men can jump both forwards and backwards.

King [edit]

When a man reaches the farthest row forward, known as the kings row or crown head, it becomes a king. It is marked by placing an additional piece on top of, or crowning, the first man. The king has additional powers, namely the ability to move any amount of squares at a time (in international checkers), move backwards and, in variants where men cannot already do so, capture backwards. Like a man, a king can make successive jumps in a single turn, provided that each jump captures an enemy piece.

In international draughts, kings (also called flying kings) move any distance. They may capture an opposing man any distance away by jumping to any of the unoccupied squares immediately beyond it. Because jumped pieces remain on the board until the turn is complete, it is possible to reach a position in a multi-jump move where the flying king is blocked from capturing further by a piece already jumped.

Flying kings are not used in American checkers; a king’s only advantage over a man is the additional ability to move and capture backwards.

Naming

In most non-English languages (except those that acquired the game from English speakers), checkers is called dame, dames, damas, or a similar term that refers to ladies. The pieces are usually called men, stones, “peón” (pawn) or a similar term; men promoted to kings are called dames or ladies. In these languages, the queen in chess or in card games is usually called by the same term as the kings in checkers. A case in point includes the Greek terminology, in which checkers is called “ντάμα” (dama), which is also one term for the queen in chess.[citation needed]

History – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Ancient games

Similar games have been played for millennia.[2] A board resembling a checkers board was found in Ur dating from 3000 BC.[4] In the British Museum are specimens of ancient Egyptian checkerboards, found with their pieces in burial chambers, and the game was played by the pharaoh Hatshepsut.[2][5] Plato mentioned a game, πεττεία or petteia, as being of Egyptian origin,[5] and Homer also mentions it.[5] The method of capture was placing two pieces on either side of the opponent’s piece. It was said to have been played during the Trojan War.[6][7] The Romans played a derivation of petteia called latrunculi, or the game of the Little Soldiers. The pieces, and sporadically the game itself, were called calculi (pebbles).[5][8]

Alquerque – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

An Arabic game called Quirkat or al-qirq, with similar play to modern checkers, was played on a 5×5 board. It is mentioned in the tenth-century work Kitab al-Aghani.[4] Al qirq was also the name for the game that is now called nine men’s morris.[9] Al qirq was brought to Spain by the Moors,[10] where it became known as Alquerque, the Spanish derivation of the Arabic name. It was maybe adapted into a derivation of latrunculi, or the game of the Little Soldiers, with a leaping capture, which, like modern Argentine, German, Greek and Thai draguhts, had flying kings which had to stop on the next square after the captured piece. That said, even if playing al qirq inside the cells of a square grid was not already known to the Moors who brought it, which it probably was, either via playing on a chessboard (in about 1100, probably in the south of France, this was done once again using backgammon pieces,[11] thereby each piece was called a “fers”, the same name as the chess queen, as the move of the two pieces was the same at the time)[12] or adapting Seega using jumping capture. The rules are given in the 13th-century book Libro de los juegos.[4]

Crowning[edit] – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

The rule of crowning was used by the 13th century, as it is mentioned in the Philippe Mouskés‘s Chronique in 1243[4] when the game was known as Fierges, the name used for the chess queen (derived from the Persian ferz, meaning royal counsellor or vizier). The pieces became known as “dames” when that name was also adopted for the chess queen.[12] The rule forcing players to take whenever possible was introduced in France in around 1535, at which point the game became known as Jeu forcé, identical to modern American checkers.[4][13] The game without forced capture became known as Le jeu plaisant de dames, the precursor of international checkers.

The 18th-century English author Samuel Johnson wrote a foreword to a 1756 book about checkers by William Payne, the earliest book in English about the game.[5]

Invented variants – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

- Blue and Gray: On a 9×9 board, each side has 17 guard pieces that move and jump in any direction, to escort a captain piece which races to the centre of the board to win.[14]

- Cheskers: A variant invented by Solomon Golomb. Each player begins with a bishop and a camel (which jumps with coordinates (3,1) rather than (2,1) so as to stay on the black squares), and men reaching the back rank promote to a bishop, camel, or king.[15][16]

- Damath: A variant utilising math principles and numbered chips popular in the Philippines.[citation needed]

- Dameo: A variant played on an 8×8 board that utilizes all 64 squares and has diagonal and orthogonal movement. A special “sliding” move is used for moving a line of checkers similar to the movement rule in Epaminondas. By Christian Freeling (2000).[17][18][19]

- Hexdame: A literal adaptation of international draughts to a hexagonal gameboard. By Christian Freeling (1979).[20]

- Lasca: A checkers variant on a 7×7 board, with 25 fields used. Jumped pieces are placed under the jumper, so that towers are built. Only the top piece of a jumped tower is captured. This variant was invented by World Chess Champion Emanuel Lasker.[21]

- Philosophy shogi checkers: A variant on a 9×9 board, game ending with capturing opponent’s king. Invented by Inoue Enryō and described in Japanese book in 1890.[citation needed]

- Suicide checkers (also called Anti-Checkers, Giveaway Checkers or Losing Draughts): A variant where the objective of each player is to lose all of their pieces.[22][23]

- Tiers: A complex variant which allows players to upgrade their pieces beyond kings.[citation needed]

- Vigman’s draughts: Each player has 24 pieces (two full sets) – one on the light squares, a second set on dark squares. Each player plays two games simultaneously: one on light squares, the other on dark squares. The total result is the sum of results for both games.[citation needed]

Computer checkers – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

American checkers (English draughts) has been the arena for several notable advances in game artificial intelligence. In 1951 Christopher Strachey wrote the first video game program on checkers. The checkers program tried to run for the first time on 30 July 1951 at NPL, but was unsuccessful due to program errors. In the summer of 1952 he successfully ran the program on Ferranti Mark 1 computer and played the first computer checkers and arguably the first video game ever according to certain definitions. In the 1950s, Arthur Samuel created one of the first board game-playing programs of any kind. More recently, in 2007 scientists at the University of Alberta[24] developed their “Chinook” program to the point where it is unbeatable. A brute force approach that took hundreds of computers working nearly two decades was used to solve the game,[25] showing that a game of checkers will always end in a draw if neither player makes a mistake.[26][27] The solution is for the checkers variation called go-as-you-please (GAYP) checkers and not for the variation called three-move restriction checkers, however it is a legal three-move restriction game because only openings believed to lose are barred under the three-move restriction. As of December 2007, this makes American checkers the most complex game ever solved.

In November 1983, the Science Museum Oklahoma (then called the Omniplex) unveiled a new exhibit: Lefty the Checker Playing Robot. Programmed by Scott M Savage, Lefty used an Armdroid robotic arm by Colne Robotics and was powered by a 6502 processor with a combination of Basic and Assembly code to interactively play a round of checkers with visitors to the museum. Originally, the program was deliberately simple so that the average museum visitor could potentially win, but over time was improved. The improvements however proved to be more frustrating for the visitors, so the original code was reimplemented.[28]

Computational complexity – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Generalized Checkers is played on an M × N board.

It is PSPACE-hard to determine whether a specified player has a winning strategy. And if a polynomial bound is placed on the number of moves that are allowed in between jumps (which is a reasonable generalisation of the drawing rule in standard Checkers), then the problem is in PSPACE, thus it is PSPACE-complete.[29] However, without this bound, Checkers is EXPTIME-complete.[30]

However, other problems have only polynomial complexity:[29]

- Can one player remove all the other player’s pieces in one move (by several jumps)?

- Can one player king a piece in one move?

National and regional variants

-

10×10 board, starting position in international draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position in English, Brazilian, Czech and Russian draughts, as well as Pool checkers

-

12×12 board, starting position in Canadian draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position in Turkish and Armenian draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position in Italian and Portuguese draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position and example play in Bashni

Russian Column draughts – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Column draughts (Russian towers), also known as Bashni, is a kind of draughts, known in Russia since the beginning of the nineteenth century, in which the game is played according to the usual rules of Russian draughts, but with the difference that the captured man is not removed from the playing field: rather, it is placed under the capturing piece (man or tower).

The resulting towers move around the board as a whole, “obeying” the upper piece. When taking a tower, only the uppermost piece is removed from it: and the resulting tower belongs to one player or the other according to the color of its new uppermost piece.

Bashni has inspired the games Lasca and Emergo.

Flying kings; men can capture backwards

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player’s near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International draughts (or Polish draughts) | 10×10 | 20 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Pieces promote only when ending their move on the final rank, not when passing through it. It is mainly played in the Netherlands, Suriname, France, Belgium, some eastern European countries, some parts of Africa, some parts of the former USSR, and other European countries. |

| Ghanaian draughts (or damii) | 10×10 | 20 | No[31] | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. Overlooking a king’s capture opportunity leads to forfeiture of the king. | Played in Ghana. Having only a single piece remaining (man or king) loses the game. |

| Frisian draughts | 10×10 | 20 | Yes | White | A sequence of capture must give the maximum “value” to the capture, and a king (called a wolf) has a value of less than two men but more than one man. If a sequence with a capturing wolf and a sequence with a capturing man have the same value, the wolf must capture. The main difference with the other games is that the captures can be made diagonally, but also straight forwards and sideways. | Played primarily in Friesland (Dutch province) historically, but in the last decade spreading rapidly over Europe (e.g. the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Czech Republic, Ukraine and Russia) and Africa, as a result of a number of recent international tournaments and the availability of an iOS and Android app “Frisian Draughts”. |

| Canadian checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | International rules on a 12×12 board. Played mainly in Canada. |

| Brazilian draughts (or derecha) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Played in Brazil. The rules come from international draughts, but board size and number of pieces come from American checkers.

In the Philippines, it is known as derecha and is played on a mirrored board, often replaced by a crossed lined board (only diagonals are represented). |

| Pool checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called Spanish Pool checkers. It is mainly played in the southeastern United States; traditional among African American players. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).[1][2]

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Jamaican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | No | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Similar to Pool checkers with the exception of the main diagonal on the right instead of the left. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Russian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called shashki or Russian shashki checkers. It is mainly played in the former USSR and in Israel. Rules are similar to international draughts, except:

There is also a 10×8 board variant (with two additional columns labelled i and k) and the give-away variant Poddavki. There are official championships for shashki and its variants. |

| Mozambican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | No | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. Although, a king has the weight of two pieces, this means with two captures, one of a king and one of a piece, one must choose the king; two captures, one of a king and one of two pieces, the player can choose; two captures with one of a king and one of three pieces, the player must capture the three pieces; two captures, one of two kings and one of three pieces, one must choose the kings… | Also called “Dama” or “Damas”. It is played along all of the region of Mozambique. In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in twelve moves or the game is a draw. |

| Tobit | 6×4 grid | 12 | — | White | Mandatory Capture and Maximum Capture | Played on a unique non-rectangular or square board of grids with 20 grid points and 18 endpoints. Played in the Republic of Khakassia. Movement and capture is orthogonal with backwards capture. The “Tobit,” a promoted piece, moves like the King in Turkish draughts. |

| Keny | 8×8 | 16 | — | Variable; Most rules have mandatory capture without maximum capture | Keny (Russian: Кены) is a draughts game played in the Caucasus and nearby areas of Turkey. It is played on an 8×8 grid with orthogonal movement. It is similar to Turkish Draughts, but has backwards capture and allows for men to jump over friendly pieces without capturing them similar to Dameo. |

Flying kings; men cannot capture backwards – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player’s near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Light square is on right, but double corner is on left, as play is on the light squares. (Play on the dark squares with dark square on right is Portuguese draughts.) | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces, and the maximum possible number of kings from all such sequences. | Also called Spanish checkers. It is mainly played in Portugal, some parts of South America, and some Northern African countries. |

| Malaysian/Singaporean checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | Not fixed | Captures are mandatory. Failing to capture results in forfeiture of that piece (huffing). | Mainly played in Malaysia, Singapore, and the region nearby. Also known locally as “Black–White Chess”. Sometimes it is played on an 8×8 board when a 12×12 board is unavailable; a 10×10 board is rare in this region. |

| Czech draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | If there are sequences of captures with either a man or a king, the king must be chosen. After that, any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | This variant is from the family of the Spanish game. |

| Slovak draughts | 8×8 | 8 | White | If there are sequences of captures with either a man or a king, the king must be chosen. After that, any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Occasionally mislabeled as Hungarian, this variant remains distinctly Slovak in origin and practice. | |

| Hungarian Highlander draughts | 8×8 | 8 | White | All pieces are long-range. Jumping is mandatory after first move of the rook. Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | The uppermost symbol of the cube determines its value, which is decreased after being jumped. Having only one piece remaining loses the game. | |

| Argentinian draughts | 8×8

10×10 |

12

15 |

No | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces, and the maximum possible number of kings from all such sequences. If both sequences capture the same number of pieces and one is with a king, the king must do.[3] | The rules are similar to the Spanish game, but the king, when it captures, must stop directly after the captured piece, and may begin a new capture movement from there.

With this rule, there is no draw with two pieces versus one. |

| Thai draughts | 8×8 | 8 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | During a capturing move, pieces are removed immediately after capture. Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there, if possible, even in the direction where they have come from. |

| German draughts (or Dame) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there as long as possible. |

| Turkish draughts | 8×8 | 16 | — | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Also known as Dama. Men move straight forwards or sideways, instead of diagonally. When a man reaches the last row, it is promoted to a flying king (Dama), which moves like a rook (or a queen in the Armenian variant). The pieces start on the second and third rows.

It is played in Turkey, Kuwait, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Greece, and several other locations in the Middle East, as well as in the same locations as Russian checkers. There are several variants in these countries, with the Armenian variant (called tama) allowing also forward-diagonal movement of men and the Greek requiring the king to stop directly after the captured piece. |

| Myanmar draughts | 8×8 | 12 | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Players agree before starting the game between “Must Capture” or “Free Capture”. In the “Must Capture” type of game, a man that fails to capture is forfeited (huffed). In the “Free Capture” game, capturing is optional. | |

| Tanzanian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Not fixed | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Captures are mandatory. When either a king or a man can capture, there is no priority. |

No flying kings; men cannot capture backwards

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player’s near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called “straight checkers” in the United States, or “English draughts” in the United Kingdom. |

| Italian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | No | White | Men cannot jump kings. A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. If more than one sequence qualifies, the capture must be done with a king instead of a man. If more than one sequence qualifies, the one that captures a greater number of kings must be chosen. If there are still more sequences, the one that captures a king first must be chosen. | It is mainly played in Italy and some North African countries. |

| Gothic checkers (or Altdeutsches Damespiel or Altdeutsche Dame) | 8×8 | 16 | — | White | Captures are mandatory. | All 64 squares are used, dark and light. Men move one cell diagonally forward and capture in any of the five cells directly forward, diagonally forward, or sideways, but not backward. Men promote on the last row. Kings may move and attack in any of the eight directions. There is also a variant with flying kings. |

Championships – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

- World Checkers/Draughts Championship in American checkers since 1840

- Draughts World Championship in international draughts since 1885

- Women’s World Draughts Championship in international draughts since 1873

- Draughts-64 World Championships since 1985

Federations

- World Draughts Federation (FMJD) was founded in 1947 by four Federations: France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland.[32]

- International Draughts Federation (IDF) was established in 2012 in Bulgaria.

Games sometimes confused with checkers variants

- Halma: A game in which pieces move in any direction and jump over any other piece, friend or enemy (but with no captures), and players try to move them all into an opposite corner.

- Chinese checkers: Based on Halma, but uses a star-shaped board divided into equilateral triangles.

- Kōnane: “Hawaiian checkers”.

See also

Notes

- ^ When this word is used in the UK, it is usually spelled chequers (as in Chinese chequers); see further at American and British spelling differences.

References – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Citations

- ^ Masters, James. “Draughts, Checkers – Online Guide”. www.tradgames.org.uk.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Strutt, Joseph (1801). The sports and pastimes of the people of England. London. p. 255.

- ^ “Error Page”. www.tradgames.org.uk. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Oxland, Kevin (2004). Gameplay and design (Illustrated ed.). Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-321-20467-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Lure of checkers”. The Ellensburgh Capital. 17 February 1916. p. 1. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ “Petteia”. 9 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006.

- ^ Austin, Roland G. (September 1940). “Greek Board Games”. Antiquity. University of Liverpool, England. 14 (55): 257–271. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00015258. S2CID 163535077. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ Peck, Harry Thurston (1898). “Latruncŭli”. Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper and Brothers. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Berger, F (2004). “From circle and square to the image of the world: a possible interpretation or some petroglyphs of merels boards” (PDF). Rock Art Research. 21 (1): 11–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2004.

- ^ Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Vol. I. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- ^ Bell, Robert Charles (1981). Board and Table Game Antiques (2000 ed.). Shire Books. p. 13. ISBN 0-85263-538-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-936317-01-9. OCLC 13472872.

- ^ Bell, Robert Charles (1981). Board and Table Game Antiques (Illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-85263-538-9.

- ^ Sackson, Sid (1982) [1st Pub. 1969, Random House, New York]. “Blue and Gray”. A Gamut of Games. Pantheon Books. pp. 9, 10–11. ISBN 0-394-71115-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ “Cheskers”. www.chessvariants.org. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Pritchard, D. Brine (1994). The encyclopedia of chess variants. Godalming: Games & Puzzles. ISBN 0-9524142-0-1. OCLC 60113912.

- ^ “Rules”. www.mindsports.nl. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Tapalnitski, Aleh (2019). Meet Dameo (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2020.

- ^ Freeling, Christian (14 April 2021). “Dameo” (PDF). Abstract Games… For the Competitive Thinker. 10 Summer 2002: 10–12.

- ^ Kok, Fred (Winter 2001). Kerry Handscomb (ed.). “Hexdame • A nice combination”. Abstract Games. No. 8. Carpe Diem Publishing. p. 21. ISSN 1492-0492.

- ^ Angerstein, Wolfgang. Board Game Studies: Das Säulenspiel Laska: Renaissance einer fast vergessenen Dame-Variante mit Verbindungen zum Schach. Vol. 5, CNWS Publications, 2002, pp. 79-99, bgsj.ludus-opuscula.org/PDF_Files/BGS5-complete.pdf. Archived 2 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 Dec. 2021.

- ^ “ФШР | Обратные шашки (поддавки)”. Федерация шашек России (in Russian). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ в 18:13, Ольга Ворончихина 27/10/2012. “Поддавки – Первый Чемпионат по игре в обратные шашки | Шашки всем”. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Chinook – World Man-Machine Checkers Champion Archived 24 June 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schaeffer, Jonathan; Burch, Neil; Björnsson, Yngvi; Kishimoto, Akihiro; Müller, Martin; Lake, Robert; Lu, Paul; Sutphen, Steve (14 September 2007). “Checkers Is Solved”. Science. 317 (5844): 1518–1522. Bibcode:2007Sci…317.1518S. doi:10.1126/science.1144079. PMID 17641166. S2CID 10274228.

- ^ Jonathan Schaeffer, Yngvi Bjornsson, Neil Burch, Akihiro Kishimoto, Martin Muller, Rob Lake, Paul Lu and Steve Sutphen. Solving Checkers, International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), pp. 292–297, 2005. Distinguished Paper Prize

- ^ “Chinook – Solving Checkers Publications”. www.cs.ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ “But Can It Type”. The Daily Oklahoman. The Daily Oklahoman. 25 November 1983. p. 51. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fraenkel, Aviezri S.; Garey, M. R.; Johnson, David S.; Yesha, Yaacov (1978). “The complexity of checkers on an N × N board”. 19th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 55–64. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1978.36.

- ^ Robson, J. M. (May 1984). “N by N Checkers is EXPTIME complete”. SIAM Journal on Computing. 13 (2): 252–267. doi:10.1137/0213018.

- ^ Salm, Steven J.; Falola, Toyin (2002). Culture and Customs of Ghana. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32050-7.

- ^ “FMJD – World Draughts Federation”.

- ^ “IDF | IDF | International Draughts Federation”.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Draughts“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–550.

External links – Digital Draughts: The Classic Checkers Challenge – JavaScript

Draughts associations and federations

- American Checker Federation (ACF)

- American Pool Checkers Association (APCA)

- Danish Draughts Federation

- English Draughts Association (EDA)

- European Draughts Confederation

- German Draughts Association (DSV NRW) Archived 27 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Northwest Draughts Federation (NWDF)

- Polish Draughts Federation (PDF)

- Surinam Draughts Federation (SDB)

- World Checkers & Draughts Federation Archived 10 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- World Draughts Federation (FMJD)

- The International Draughts Committee of the Disabled (IDCD) Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

History, articles, variants, rules

- A Guide to Checkers Families and Rules by Sultan Ratrout

- The history of checkers/draughts

- Jim Loy’s checkers pages with many links and articles.

- Checkers Maven, CheckersUSA checkers books, electronic editions

- The Checkers Family

- Alemanni Checkers Pages

- On the evolution of Draughts variants

- “Chess and Draughts/Checkers” by Edward Winter

Online play

- mindoku.com Play online draughts, Russian draughts or giveaway draughts. Online tournaments every day.

- Server for playing correspondence tournaments

- A free program that allows you to play more than 20 kinds of draughts

- A free Application that allows you to play 15 popular checkers variants with a human or a computer

- Draughts.org Play online draughts plus information on strategies and history.

- Lidraughts.org Internet draughts server, similar to the popular chess server lichess.org

Related Posts:

The Memory Game VB.NET setup install package

Unveiling the Top 1000 Google Queries: Insights into Global Curiosities and Search Trends

Learn about programming Loops in Python

Visualizing Key Programming and Algorithm Concepts: A Comprehensive Guide with Diagrams

JBD After hour notary – afterhournotary.com

Hotel front desks are now a hotbed for hackers

15 Hidden Windows 10 Features You Need to Know: Boost Productivity and Efficiency